Honor Zetzer's open-door policy

What's an authentic persona? Is the L.A. River beautiful actually?

Honor leads the way to the lake. The sun is out on a Friday afternoon and the people mulling around the park with us are sopping it up after a gray spell. Spring is having no identity crisis: goslings sputter into the lake, brandishing fuzzy yellow heads; flowers bloom effusively along sidewalks of grime; denizens wear shorts and skirts but light jackets in apprehension of the lingering chill; couples pedal picturesque swan boats on the water.

Spring greets the city as foreplay for summer, as a jigsaw falling into place so gently but smirking smug all the same with teases of drizzle and May gray just when you think you’re in the clear after winter’s gloom. The season of rebirth remains rooted in its persona, even when the sunshine wavers behind an overcast day.

In a way everything is so classically springtime that the scene feels trite and overplayed. But I’m walking with Honor Zetzer, so there are mysteries to be unraveled, our conversation unspooling behind us like a thread to eventually follow back home.

From an up-close observer’s standpoint, I’ve witnessed Honor begin to morph. Not into something inauthentic, but in the way that any of us shapeshift through periods of self-discovery. First they pierced their eyebrow, then cut their long honey hair over the bathroom sink to a sharp edge above their shoulders. Soon after, they made the starkest change by dying their hair a dark brown, nearly black, a move that brought out the warmth in their equally brown eyes.

Tenets of Honor’s spirit have evolved in tandem. Their once-held tongue has been replaced by a blunt openness, an unapologetic freedom of expression.

It feels like Honor, like most artists of the times, has adopted a level of persona, though the pieces were all there, beneath the soil.

“Every persona is just certain elements played up, right?” Honor posits. “I think it’s about whether you’re choosing the right elements, and do those elements feel like they actually resonate. If you really believe in your persona, then the embodiment of the persona is an authentic expression.”

Is it an oxymoron to say “authentic persona”? Audiences are transfixed by personas, partially for the allure of never quite knowing what’s behind the curtain. The artist’s character gives us something to latch onto, viewers jamming a finger between the ribs of perceived insincerity and deeming them “fake,” walking away with an undeserved air of superiority. An authentically presented persona only becomes so obvious when the artists sheds their skin, David Jones into Bowie into Major Tom to Ziggy Stardust and eventually back to Bowie. A persona has to come from true expression, or it’s just a mask.

On our second or third lap around the lake, Honor relays the story of how they came to L.A., leaving an Ohio driveway alone in a packed Prius and emerging on the West Coast five days later, seeing the L.A. skyline for the first time after flat America and desert horizons. Back then, in late summer three years ago, they looked the same as when we first met: long honey brown hair, baby bangs, serious features blanketed over a warm caramel center. Below the litany of recent physical alterations, the center remains the same. Sincere, authentic.

I must’ve heard the story before, must’ve because I’ve known Honor for, what, two years? But I didn’t recall that Honor had never stepped foot in L.A. before deciding to move here, not once. A promised land, like promises so easily broken by the disappointment of a vision unrealized. But miraculously the vision hasn’t been punctured. Honor says the words we all keep on the tip of our tongues, hoping they’ll be true enough one day to utter: that things have turned out the way they hoped.

We stop to watch yellow-headed ducklings and goslings snuff around in the patchy grass alongside the man-made lake. I ask aloud whether the Honor that drove up to the city three years ago had imagined that this would be their life now.

“I wouldn't have pictured it exactly this way. But the vibes are there,” Honor says. “I think I was thinking, ‘I’m going to move to L.A. and I want to be around creative people, and I want to be writing.’ And that is what's happening.”

Since February Honor has been hosting the alternative literary reading series Vermicult. Spearheaded by Honor in collaboration with roommate Sarah Miller, the Vermicult was cultivated in response to the repetitive and clique-ish nature of the existing alt lit scene in Los Angeles. Honor frequents literary readings around town; after attending a particularly droll one late last year, the idea for their own reading series for poetry, prose, and short essay began germinating. A couple months later, the first reading sprouted, packing Honor and Sarah’s living room with strangers and friends, the result of Honor’s guerilla marketing (posters taped around urban hubs), word of mouth, and, as is customary, social media.

At that inaugural meeting, Honor read an introduction to the audience crammed on the couches and spilling along the floor into the kitchen. In the introduction, Honor likens artists to worms: soft and armorless, multi-hearted, eating it all up and spitting it out. “The poet, the worm, creates something out of something else... In a compost heap, there are no spectators, and the same is true in The Vermicult, and the same is true of the world. We are all here in the same mess. We all have to help digest at least a bit of it and see what we can turn it into.”

After that, Honor’s status as Vermicult leader calcified. Word spread. At another literary event a few weeks later, strangers approached to introduce themselves to Honor Zetzer of Vermicult (I say as witness).

Vermicult’s April reading necessitated an outdoor space for Earth month, somewhere slightly jarring, as nature in the polluted muck of city can be. Honor and Sarah chose a spot beside the L.A. River, in a clearing just off the bike path in Frogtown. Location details were shared to attendees via coordinates. As the reading began, a light drizzle fell, and by the time Charlie Stuip had finished reading, a rainbow backlit the scene, which teemed with activity like the river itself. The readers’ voices had accompaniment from bicyclists’ bells, Doppler-effected boomboxes, children at play, dogs ahowl, herons cresting. Passersby stared openly at our congregation.

Honor chose the river for its juxtapositions, its dystopic atmosphere where nature fuses with the urban world. Great blue herons hunt for living matter amongst floating garbage. Mounds of plastic and metal litter the freshwater reeds. Looming trees somehow sprout from the concrete riverbed, often parched. The river is a weird place in Los Angeles, Honor says, evoking questions like “where are we?”

“I just think the river is very dystopian, you know?” they say. “It's this channeled, weird, natural thing that was turned completely unnatural.”

And Vermicult embodies that unsettling oddity, the transgressive existential unease. The compendium of readers chosen each month often pull from a place examining, as Honor articulates it, “the weirdness of, like, what the f— are we doing?” Readers are often poached from other literary circles in L.A., or occasionally Honor’s own friend group, with poetic voices that conjure ideas attempting to worm past the conventional. Again, this is a reading group born from a dissatisfaction with existing reading groups. The bar is high, the scene must be curated. If “scenes” exist now, they’re rarely spontaneous anyway.

“I think we lean too much on the Internet. It kind of stops us from really having scenes. Scenes require this constant — speaking from my wise breadth of knowledge at less than a quarter century old — scenes require people to be around each other all the time,” Honor says. “Something I hear about a lot when I'm reading about great artists from the past: they were all going to each other’s houses all the time.”

The artist immediately in reference is David Bowie, whose biography Honor has been engulfed in. His boisterous social circle was perpetually crashing at his place in Beverly Hills or New York, tinkering with whichever medium was the order of the day.

“I feel like people forget to just be around each other, doing art around each other, because the Internet makes it so easy to connect without having to be next to each other,” Honor says, pulling out their flip phone. (Everyone who sees Honor’s “dumbphone” goes, “oh, I need one of those.” What does that say about us, everyone that wants to downgrade and yet probably never will?)

I stoop to tie my shoelace. “Yeah. If we didn't have social media, people would be so much more bored and be like, ‘Hey, I'm coming over.’”

“Exactly. Just ring my doorbell, like, straight up,” Honor declares. “I want to be hanging out at home and someone rings my doorbell. If we don't answer, we're not home.”

An open-door policy feels like childhood, reminiscent of biking to your friend’s house down the street to kill time. I ask if, as a kid in Cleveland, Honor had friends who lived nearby to play with. They admit to mostly playing outside alone, sometimes just spending an afternoon throwing a ball in the air and catching it. We agree more time should be spent like that. The other day Honor came over and we sat on the couch with our friends just listening to music, barely speaking, soaking it in.

A little sick with nostalgia, I ask what Honor thinks everyone is after these days, why we’re so isolated as a generation.

“What is everybody after? Love,” they say definitively. “Why are we so isolated? Because we're all after love, and we don't know how to get it, and it kind of feels like it's a battle to get the amount of love that you're looking for. You start to kind of feel like it's you against the world.”

At the core: a feeling of belonging. Stability.

“It's kind of like a doom spiral,” Honor says. “You feel like you can't access it, so you start to feel like you need to become a certain way to access it, or like there are certain things that you can do to access what feels like it. And then, because you're doing those things, you start to feel more and more isolated, like you're putting on a front. So then people don't see the real you.”

Despite the doom spiral, Honor has felt the most sense of belonging in L.A. than anywhere else. But they do still feel this sense of urgency, “like it could fall away at any point.”

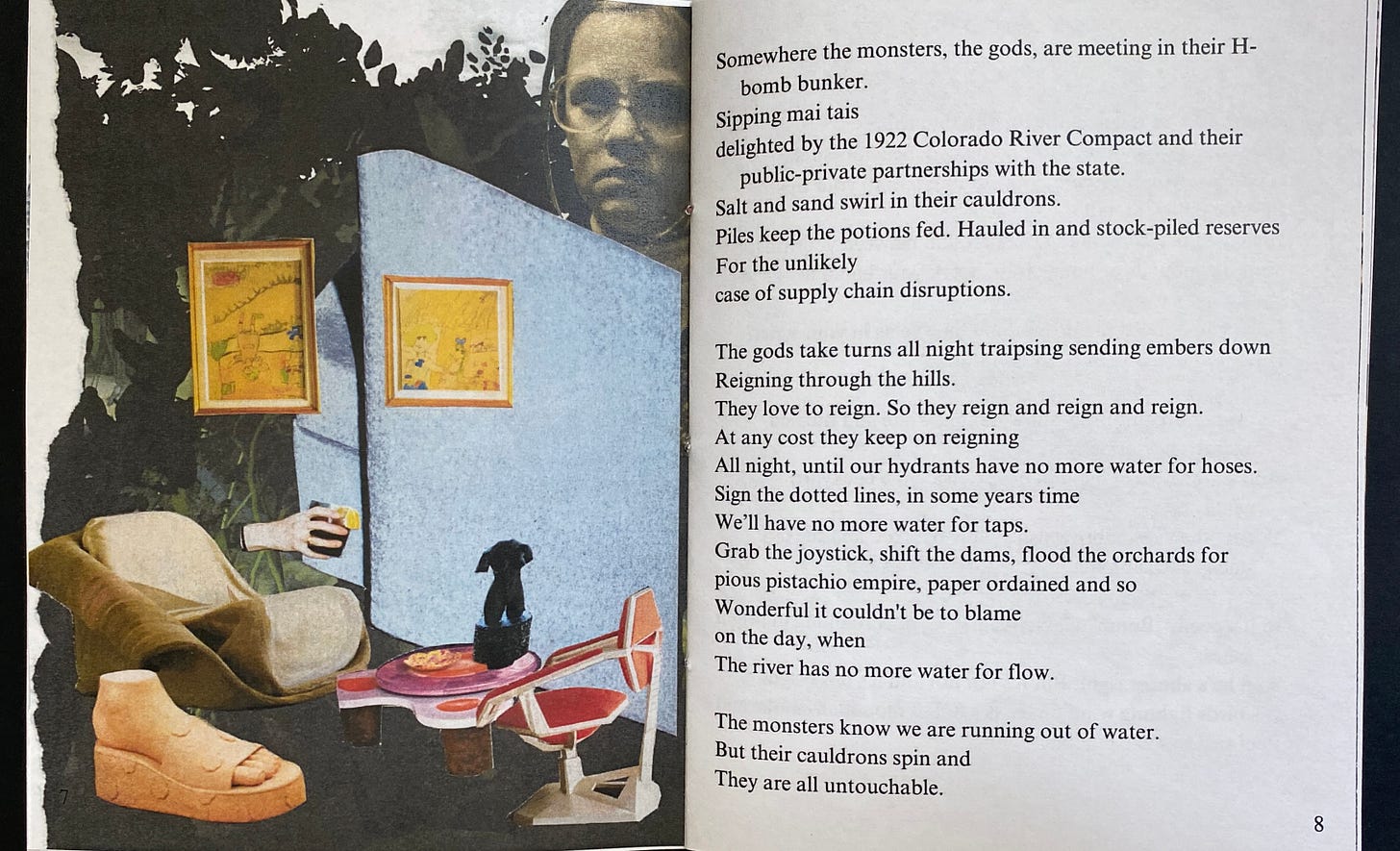

Lately they’ve been making zines, selling their latest to bookstores in Echo Park. Mediums beyond simple pen-to-paper prose (Honor requires Vermicult readers to eschew phones and read from paper) have always called to Honor, and the zine, “Woke Up Burning,” is hand-bound with a hand-painted cover, filled with collage and poetry created in response to L.A.’s January fires. Balancing tones of and themes of outrage, existential uncertainty, and disillusion, Honor’s work is a self-portrait of this sense of urgency, reading like a mix of Allen Ginsberg and Fiona Apple.

There’s an exasperation to Honor’s prose: “You can cry and cry and cry / Until your body has no more water for tears. / You can spin in your swivel chair / Ripping your hair out, spitting / Until your body has no more water for drool.”

They finished the zine this while working two jobs and submitting work to other publications, recently landing pieces in ExPat Press and Unlikely Stories.

“Woke Up Burning” conveys a sense of frenziedness not unlike that of Bob Dylan, Honor’s patron saint in union with Jack Kerouac and the Beats, all notably tied up in their own crafted personas, the subjects of debate and dispute regarding their authenticity as artists and icons.

“I’m always interested in the concept of ‘the voice of a generation,’” Honor says. We’re walking along a busy boulevard near the lake and I’m straining to hear their voice over the din of traffic. “There's an element of persona that you have to accumulate. There is something to say for the way that people were able to make people think they were really cool and had good ideas.”

“I feel like that's especially easy to do now with the Internet,” I add. “But then it's also oversaturated, because everyone starts to build a persona—”

We stop, spotting a lone magazine page stuck wet to the sidewalk. The headline reads: What If Bob Dylan Wanted To Be A Rocker All Along?

Honor wasn’t shy as a kid, not until their tween years. There was a period they refer to as The Golden Days, between ages five to eight, where they felt completely free, like: “I’m crazy!”

“Do you have a sense of wanting to get back to that?” I ask.

“I feel like I am getting back to that.”

“Yeah, I feel like you are too.”

Find Honor Zetzer at @epicreztez and @vermicult.la. “Woke Up Burning” can be found at Stories and A Good Used Book in Echo Park. They’re currently editing their first novel, and also once walked the Camino de Santiago in Spain, which they should talk about more.

First Name Basis is Izzy Sami’s bridge between journalistic integrity and personal relationships, pushing the definition of “conflict of interest.” Profiles of people she meets out in the world are published once a month, twice a month if she gets a grip on her time management skills, and not at all if her subject ghosts her.

beautifully written!

This is so wonderful!!!